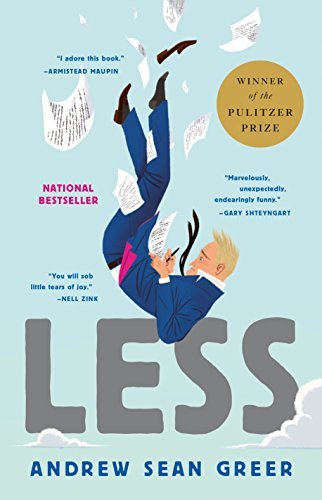

I “read” LESS as an audiobook, which may have affected how it worked on me. Though a short book, it took weeks to get through, chiefly because of all the limits when I allow myself to listen to an audiobook. (Mostly I listen in the gym — but then I got Covid and stopped going to the gym. On walks — but only when alone, because otherwise it’s antisocial. Not in bed at night, because I fall asleep and miss things. Not on my commute, because I am unreasonably afraid of an earbud falling out of my ear and into some irretrievable place. Etc.) So I kept putting it aside for days at a time and then returning to it, yet somehow never lost the thread. This might be in part because of its episodic nature, as I discuss more below.

LESS is laugh-out-loud-with-an-undignified-snort funny in places. (I had to suppress this impulse in the gym.) It is also lyrical. Andrew Sean Greer has a master touch with unexpected metaphors and similes, with descriptions that pierce your heart with their rightness. He writes well about love and longing and nostalgia. But anyone who writes about such topics, however well, risks descending into self-indulgent bathos, into sweet sentimentality. The humor is the lemon juice or the lemon zest that is supposed to keep this from happening. Did this work? Mostly, it did.

The structure is fairly simple, as the chapter headings make clear (Less at First, Less Mexican, etc). Arthur Less, in order to escape the wedding of the man he has (too late) realized he truly loved to another man, is traveling around the world courtesy of a series of decreasingly probable writerly events. (He’s a novelist, whose latest novel has been rejected by his publisher.) Everywhere he goes, disaster threatens but never quite strikes. It is not so much the rising action of a conventional novel as a picaresque — a series of episodes, rather than one thing leading to another. Although it is true that certain motifs recur, which does offer a sense of things being completed. The journey is mostly into himself, into the reality of getting older as a once-beautiful young man, facing age and time and the specter of death.

This book got a lot of prizes and acclaim and presumably sales. I always cheer when a book that dares to be funny instead of tragic manages that.